The Right Place at the Right Time: Recovery of North Atlantic Right Whales

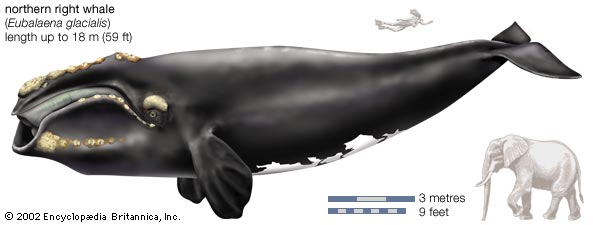

North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) were voraciously hunted for centuries. These whales were the perfect target for shore whalers: they stayed close to shore, swam slowly, and floated upon death. These attributes caused the species to nearly go extinct, until they became the first cetacean species to receive protection after the First Convention for the International Regulation of Whaling in 1931. These whales have been protected from whaling since the implementation of the Convention’s ruling in 1935, but the population has been unable to fully recover. This is largely due to the growth of the shipping industry. In the past 50 years, the number of commercial shipping vessels has tripled, and the size of these vessels has increased by a factor greater than six. This growth has led to numerous collisions between whales and ships, making it the leading cause of mortality for E. glacialis. However, things are starting to look up for right whales.

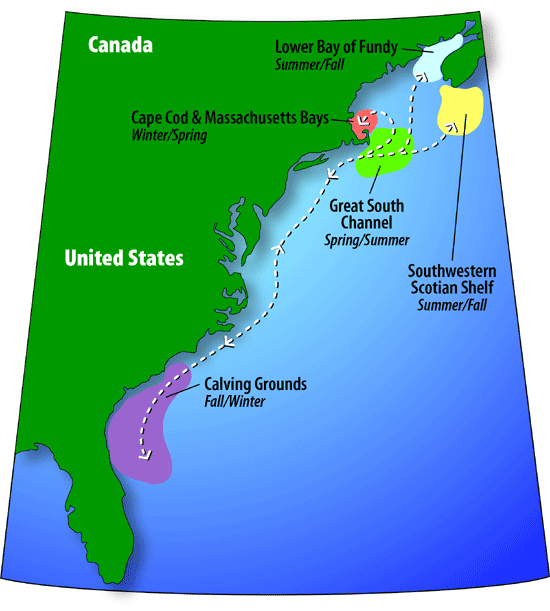

Habitat Area

In 2003, Canada decided to move the shipping lanes transecting the Bay of Fundy four nautical miles to the east, taking the ships out of critical feeding grounds for right whales, and reducing the potential for collision by 80%. This unprecedented ruling was brought about by a very unlikely partnership: an aquarium and an oil company. Irving Oil has the largest shipping fleet within the Bay of Fundy, but worked with many different groups within both Canada and the U.S. in the hopes of increasing conservation measures for E. glacialis. With their complete support of these measures, the shipping lanes have been successfully moved, with negligible impacts on the shipping companies.

The U.S. followed Canada’s example in 2007, shifting international shipping lanes out of areas within the Gerry E. Studds Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary where right whales congregate. The U.S. furthered their protection of E. glacialis by implementing a 10 knot speed restriction for vessels over 20 m in length in 2008, making it permanent law in 2013. This speed restriction has reduced the risk of collisions between right whales and ships by 80-90%.

Because of these implementations, right whale numbers have increased from 350 individuals in 2003 to 450 in 2012, with an average annual rate of increase of 2%. The number of calves per year has also increased from 11 (in 2001) to approximately 22 every year. In fact, Dr. Moira Brown of the New England Aquarium has said that as of 2012, no known collisions with right whales have occurred in the Bay of Fundy. Moving the shipping lanes and providing speed restrictions are not the only measures that have been taken for the conservation of E. glacialis, however.

In order to further reduce the number of ship strikes occurring within the U.S., the Cornell Bioacoustics Research Program, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association have collaborated to create Right Whale Listening Network. These organizations have placed acoustic buoys within shipping lanes to detect the vocalizations of right whales. When a call is heard, it is analyzed by a research lab to confirm the presence of a right whale. If it is a right whale, an alert is sent to ships located near the source of the sound so they can take necessary precautions to avoid a collision.

The increase of E. glacialis shows the world that it is both possible and plausible to conserve this species with minimal impact on our own lives. If these measures are used as a precedent for other countries to conserve their whales, it is probable that we might just be able to save numerous species. If these implementations can work for the U.S., they can work for just about everywhere else.

Article by Hillary Ballantine:

Hillary Ballantine is from a small town in central Ohio, a long way from the ocean. She became mesmerized by marine life at a very young age, and always knew she wanted to help save the whales. She graduated from Coastal Carolina University with a B.S. in Marine Science and a B.S. in Biology, and is currently attending graduate school at Antioch University New England, earning a M.S. in Environmental Studies with a concentration in Conservation Biology. She has worked with educating the public on marine life at Myrtle Beach State Park, and hopes to further her experience in both the education and scientific aspects of conservation.